Latin was the language of the Romans. But it was also much more. It was the language of the elites and eventually also the ordinary people of the entire western Roman Empire. The western Church adopted Latin as its official language, and maintained it long after the western Empire broke up in the fifth century AD, as the language of religion, scholarship and science. Hence Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton and many other ground-breaking thinkers wrote their works in Latin, which remained the language of international science right down to the nineteenth century.

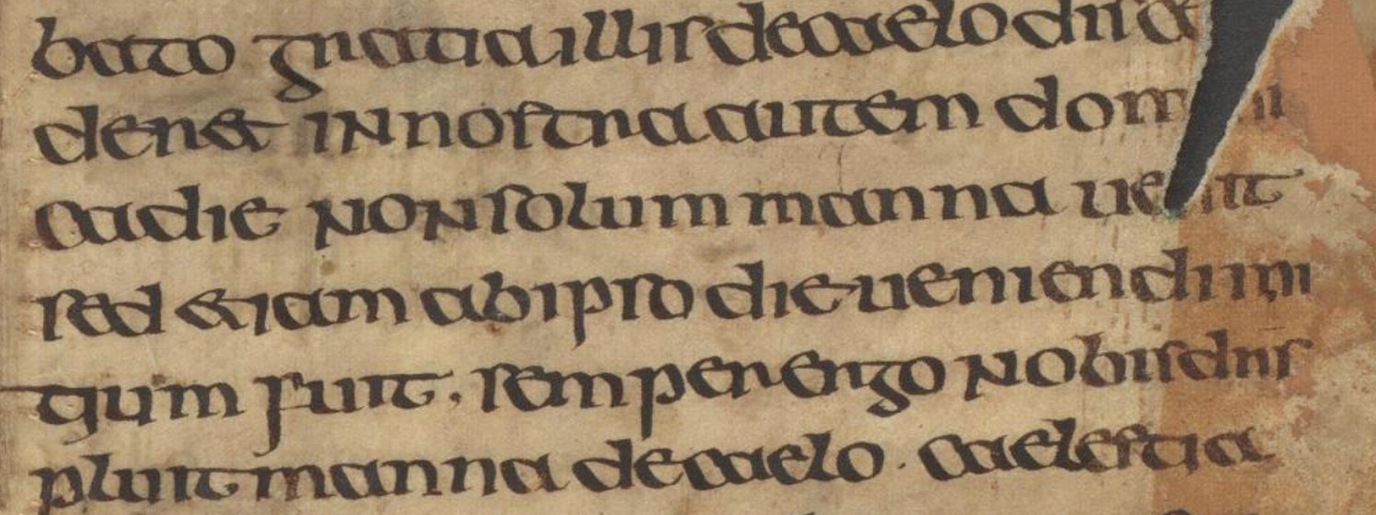

The prestige of Latin language and culture meant that it had a major impact on the local cultures that encountered it. When Christianity came to Ireland around the fifth century, its most famous apostle, Patrick, wrote in Latin the first surviving documents from Ireland, his Confessio and Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus. Irish scholars embraced Latin to the extent that many later travelled to the Continent and taught Latin there. Naturally, then, Latin had a significant impact on the Irish language as well.

Cognates versus loanwords

Before we explore some Latin words borrowed into Irish, we should first recognise that some connections between Irish and Latin run much deeper. Both languages are part of the very ancient family of languages known as Indo-European, which stretches all the way from Ireland to India, and includes Greek, as well as Germanic, Slavic and Iranian languages, and many others. For example, we could compare Irish aon, dó, trí, ceathair ‘one, two, three, four’ with Latin unus, duo, tres, quattuor, Russian odin, dva, tri, chetyre, Persian yek, do, se, chahār, or Sanskrit éka, dvá, trí, catúr. Since the early nineteenth century, linguists have understood that some such similarities reflect shared ancestral relationships rather than direct language contacts.

Loanwords, by contrast, are words that one language takes directly from another. (We refer to this process as ‘borrowing’, even though loanwords are never given back!) English has an enormous number of loanwords, up to 75% of its vocabulary on some estimates, coming mostly from French and Latin.

Motivations for borrowing vary. Some loanwords designate brand new things and ideas introduced from abroad (e.g. croissant, hummus, pizza, sushi, tandoori). Others reflect the high status of international cultures. For example, animal names in English are often Germanic in origin (e.g. cow, calf, deer, pig, sheep), but the names of their meats come from French (e.g. beef, veal, venison, pork, mutton), reflecting the superior prestige of French cuisine.

Christian concepts and associations

It should come as no surprise that many Irish borrowings from Latin reflect core Christian concepts: words like aifreann ‘Mass’ from offerenda ‘offerings’, aingeal ‘angel’ from angelus, altóir from altar, aspal (Old Irish apstal) ‘apostle’ from apostolus, beannacht ‘blessing’ from benedictio, cros and croch ‘cross’ both from crux, diabhal ‘devil’ from diabolus, ifreann ‘hell’ from infernus, and peaca (older spelling peacadh) ‘sin’ from peccatum.

The personnel of the Church retained their Latin titles in Irish, as in easpag (Old Irish epscop) ‘bishop’ from episcopus, sagart ‘priest’ from sacerdos, and manach ‘monk’ from monachus. The names of Church locations similarly: eaglais ‘church’ is from ecclesia (whence English ecclesiastic), cill ‘church’ from cella ‘(monk’s) cell’, díseart ‘retreat, hermitage’ from desertum (a metaphorical desert, inspired by stories of the monks of Egypt), mainistir ‘monastery’ from monasterium, and teampall ‘churchyard’ from templum.

Many other words reflect looser Christian associations: for example, corp ‘body’ from corpus, obair ‘work’ from opera, pian ‘pain’ from poena ‘punishment’, pobal ‘people, community’ from populus, reilig ‘graveyard’ from reliquiae ‘remains’, trioblóid ‘trouble’ from tribulatio. Saol ‘life’ (older saoghal) is derived from saeculum, meaning ‘human lifetime’. (The same Latin word is the origin of French siècle ‘century’ and English secular, referring to human as opposed to religious affairs.)

It should be noted that several of these core Christian terms were not originally Latin at all, but Greek words in origin. Christianity first established itself in the eastern Mediterranean region, where Greek was the international language, which is why early Christians wrote the New Testament in Greek. For the earliest Roman Christians, therefore, Greek words like angelus, apostolus, diabolus, ecclesia, episcopus, monachus may have sounded as exotic as they later did when brought to Ireland in Latin form.

Literacy and education

Given that books were first introduced to Ireland with Christianity, it should be no surprise that most of the terminology of literacy is Latin in origin. Leabhar ‘book’ comes from liber, litir ‘letter’ from littera, léann (older léigheann)‘learning, study’ from legendum ‘reading’, peann ‘pen’ from penna (originally meaning feather, used to make quills), scríobh ‘write’ from scribo, caibidil ‘chapter’ from capitulum, and údar ‘author’ (older ughdar) from auctor.

Education is another area where we might expect to find influence: ceacht ‘lesson’ from acceptum ‘something received’, ceist ‘question’ from quaestio, intleacht ‘intellect’ from intellectus, meabhair ‘mind, memory’ from memoria, riail (older riaghail) ‘rule’ from regula, scoil ‘school’ from schola.

Some Latin words and phrases underwent transformations during the borrowing process. For example, tearmann ‘sanctuary’ was borrowed from terminus, meaning ‘boundary’, but understood to refer to the boundary of a church or monastery where sanctuary could be sought. Paidir ‘prayer’ is a clipping of pater noster, the opening words of the ‘Our Father’, extended to any kind of prayer. Similarly, long ‘ship’ is a shortening of navis longa ‘long ship’, where navis was originally the key word. (The derived term loingeas ‘fleet’ inspired the name of our national airline.) Another transformation is seen in the word póg ‘kiss’, which comes from Latin pax ‘peace’, referring to the osculum pacis ‘kiss of peace’ offered between Christians.

Organisation of time

Monastic life involved a highly rigorous organisation of time around the daily prayers of the Divine Office (Latin officium ‘duty’, from which oifig). This is still reflected in the terminology of time in Irish today: uair ‘hour’ derives from Latin hora and seachtain ‘week’ (Old Irish sechtmain) from septimana. Similarly, maidin ‘morning’ comes from matutinus, and tráthnóna ‘evening’ is from a compound of Irish tráth ‘time’ and nóna from Latin nona ‘ninth (hour)’, i.e. the ninth hour after dawn, when monks would assemble for mid-afternoon prayer.

The names of days of the week are partly borrowed ancient Roman days, which were named after heavenly bodies. Dé Luain ‘Monday’ (or ‘Moon day’) is modelled on Dies Lunae (using native Irish words, however). Máirt ‘Tuesday’ and Satharn ‘Saturday’ are borrowed from Dies Martis and Dies Saturni (the days of Mars and Saturn). But since Friday was a Christian day of fasting, Aoine ‘Friday’ was used instead, derived from ieiunium ‘fast’. Céadaoin ‘Wednesday’ meant ‘first fast’ (monks were keen on fasting!) and Déardaoin ‘Thursday’ was a day of respite idir dá aoin ‘between two fasts’. Domhnach ‘Sunday’ is from Dies Dominicus ‘the Lord’s day’. The months of the year are similarly mixed, this time between ancient Roman and native Irish names, culminating in Nollaig from natalicia ‘birthday festivities’ for the month in which Christmas falls.

Transformations and influences

Linguists studying the forms of these borrowings have been able to identify different chronological layers. For example, at the time of the arrival of Christianity, Irish is known to have lacked the sound p. So Latin words like Pascha ‘Easter’ would have been tricky for Irish speakers to get their mouths around, and they approximated the sound of p with the sound qu (with lips rounded), later simplified as c. Hence Pascha became Cáisc in Irish, and similarly we have clann ‘family’ from planta ‘sprout, shoot’ (used in the more general sense ‘offspring’), and cailleach ‘old woman, hag’, based on caille ‘veil’ from pallium ‘cloak, covering’ (referring to the veil worn by married women and nuns).

We can also detect clear influence from British Celtic in many early borrowings. For example, Nollaig in Old Irish was written Notlaic, but pronounced very similar to Nadolig in modern Welsh, a language descended from ancient British Celtic. Similar traces in words such as obair, pobal, póg, sagart and saol indicate that not only Patrick but also many of his countrymen came from Britain to Ireland as missionaries, and taught Latin with a distinctive accent that persisted long after Christianity took root here.

The legacy of Latin in Irish today

The sixty or so Irish words of Latin origin mentioned above are just the tip of the iceberg. The Wiktionary category ‘Irish terms derived from Latin’ currently lists 970 words in total, and each word has its own story to tell.

A learner of Irish today might easily assume that most familiar-sounding words are recent borrowings from English. That is far from true, however. Most of the Irish words listed here are already attested in the eighth or ninth century, during the Old Irish period, and many were probably in use much earlier.

At the University of Galway, the discipline of Classics in currently engaged in several projects that trace the influence of Latin culture on early Irish language, literature and thought. Among them, Dr Jasmim Drigo is working to carry out a full assessment of the Latin borrowings in Old Irish. Her work will shed further light on the fascinating interactions between these languages and cultures.

A shorter version of this article was published on RTÉ Brainstorm.